The rise of photography as an artistic discipline during the 19th century inspired multiple generations of photographers to experiment with various techniques to improve long exposure times and image quality. Surely these were the beginnings of William Mumler, who went on to produce multiple photographs of spirits throughout his career and went down in history as the doyen of ghost photography.

SEE ALSO: 7 Stories of People Waking Up After Being Declared Dead

The big business of spirit photography.

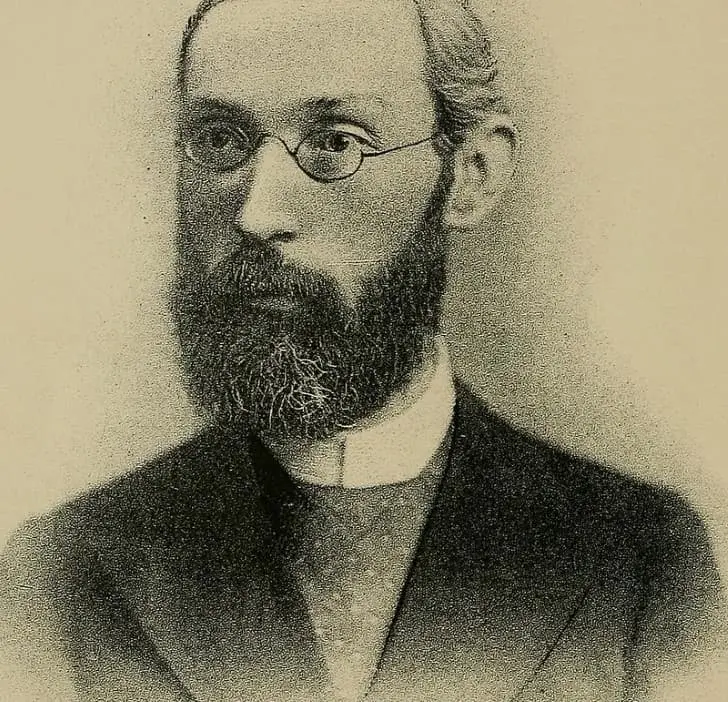

Mumler was born in 1832 and began as an ornament engraver in Boston, United States. However, this man’s true passion was photography, which at that time was beginning to consolidate. The first photograph of a ghost he obtained, in his own words, resulted from an accident while testing new chemicals to develop a photographic plate in a friend’s studio.

After taking a photograph of himself (did you think the selfie was a modern invention?), he almost goes backwards when he develops it and finds a woman sitting next to him. According to the story published in a local newspaper on November 21, 1862, detailing Mumler’s strange pastime, he mentioned experiencing a “peculiar sensation of trembling in his right arm” while holding the image he had just revealed. Afterward, he was overcome by an intense sense of exhaustion. Upon first looking at the photograph, he not only concluded that he had captured a ghost, but identified it as the spirit of a deceased cousin.

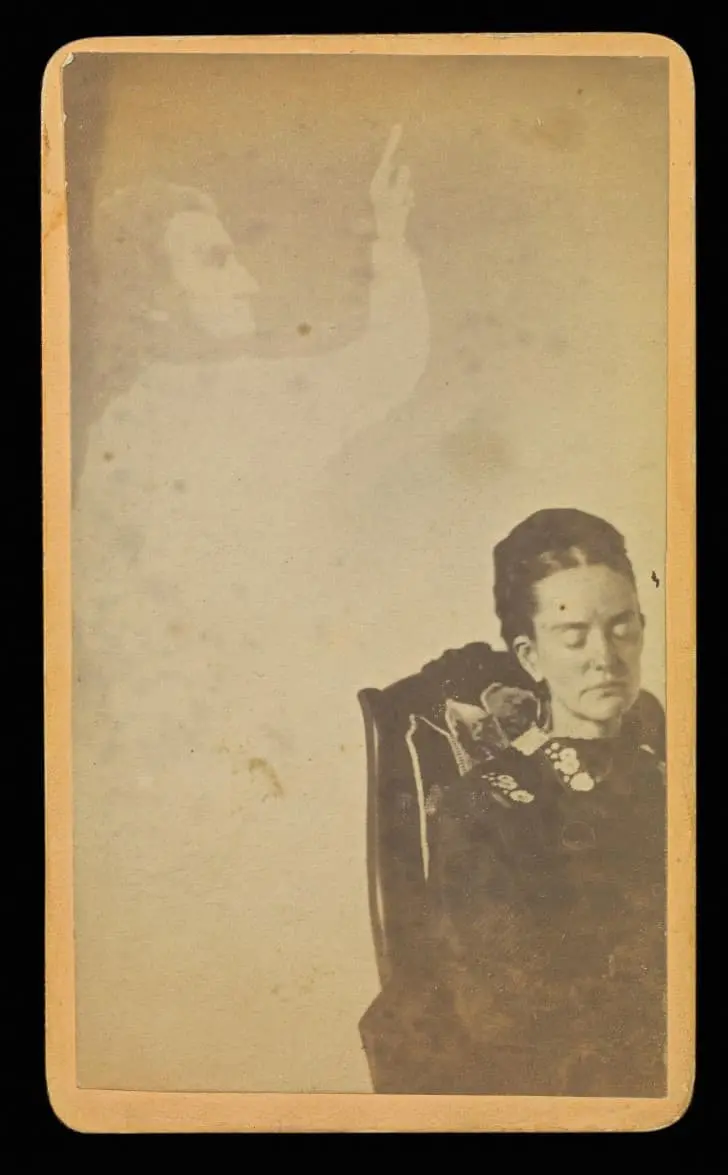

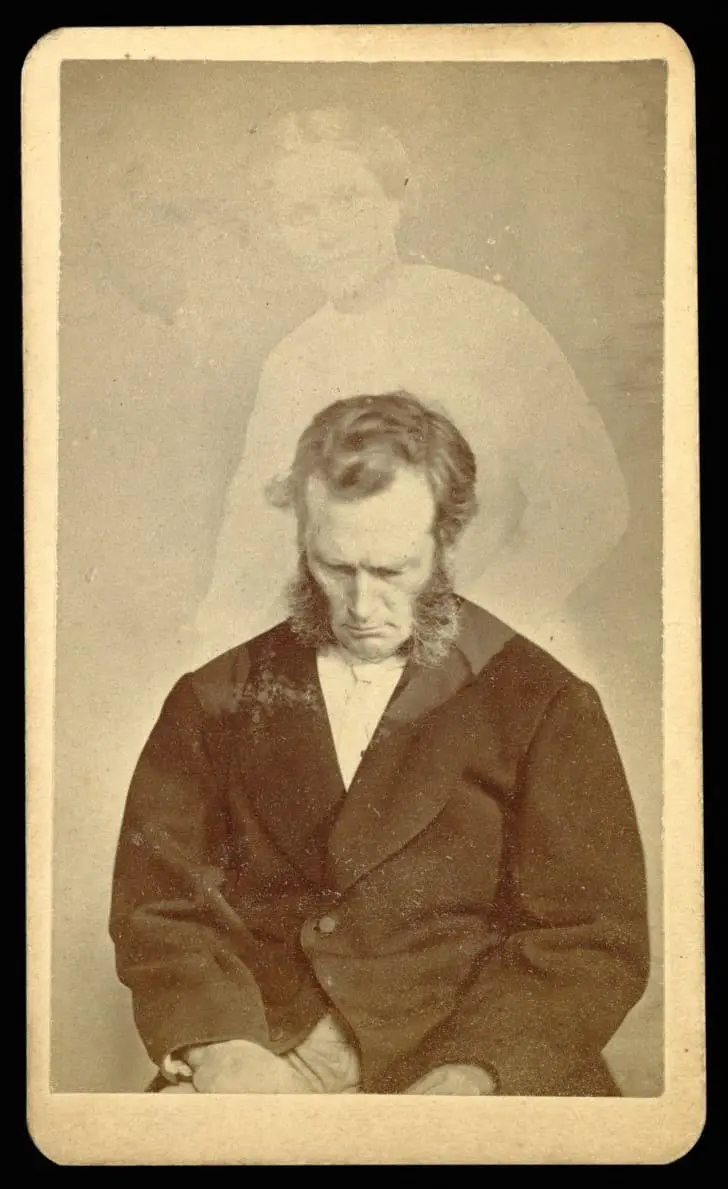

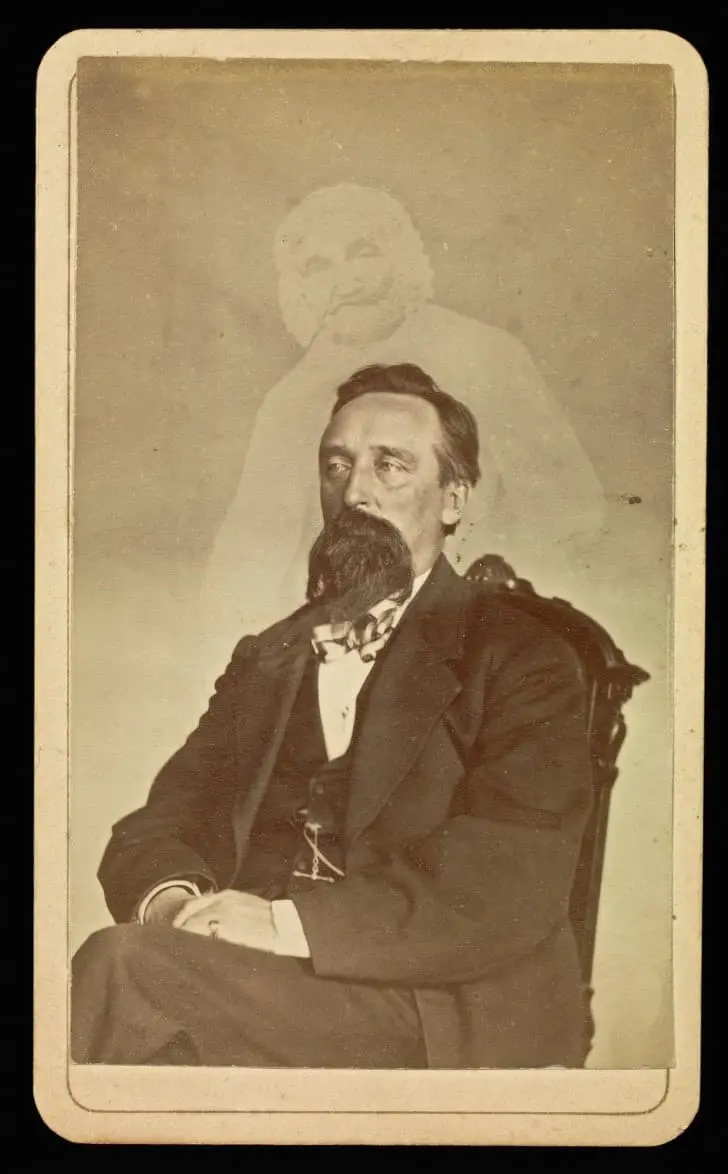

Inquiring about their experience with some spiritualists in the city, these individuals took advantage of the discovery and requested photographs of themselves. Among several dozen photographs Mumler took, only a few revealed additional images of individuals the spiritualists recognized as deceased family members or acquaintances. Overall, the quality of these photographs was much more precarious than what Mumler could achieve with live models. What’s more, there were people who requested multiple photographs, but the ghostly characters revealed were rarely the same.

A well-crafted hoax.

For many, Mumler’s discovery was a revelation. The arguments of spiritualism seemed to be consolidated by finding a way to prove existence beyond death. Imagine people’s excitement at knowing that their relatives, whom they thought they had lost forever, surrounded them all the time in their ghostly form. They were so delighted with this idea, that they simply rejected any suggestion that there might be any trickery behind it.

Dr. Ammi Brown, a supporter of William Mumler, told reporters that he had personally examined the photographer’s device without finding any evidence to suggest fraud. As if that were not enough, he added: “If these photographs, supposedly images of spirits, are a scam, it is a hoax that surpasses the ingenuity of all conjurers and necromancers of the present and past.”

After some skeptics accused Mumler of generating his photographs of ghosts by double exposure on photographic plates, he invited them to bring their own plates to the experiments, and sure enough, the spirits continued to appear on the developed plates. While some photographers reproduced the ghostly effect by superimposing two negatives and developing them in the same photograph, apparently no one was able to explain how Mumler could achieve the same thing with a single plate.

Photographs, ghosts and art.

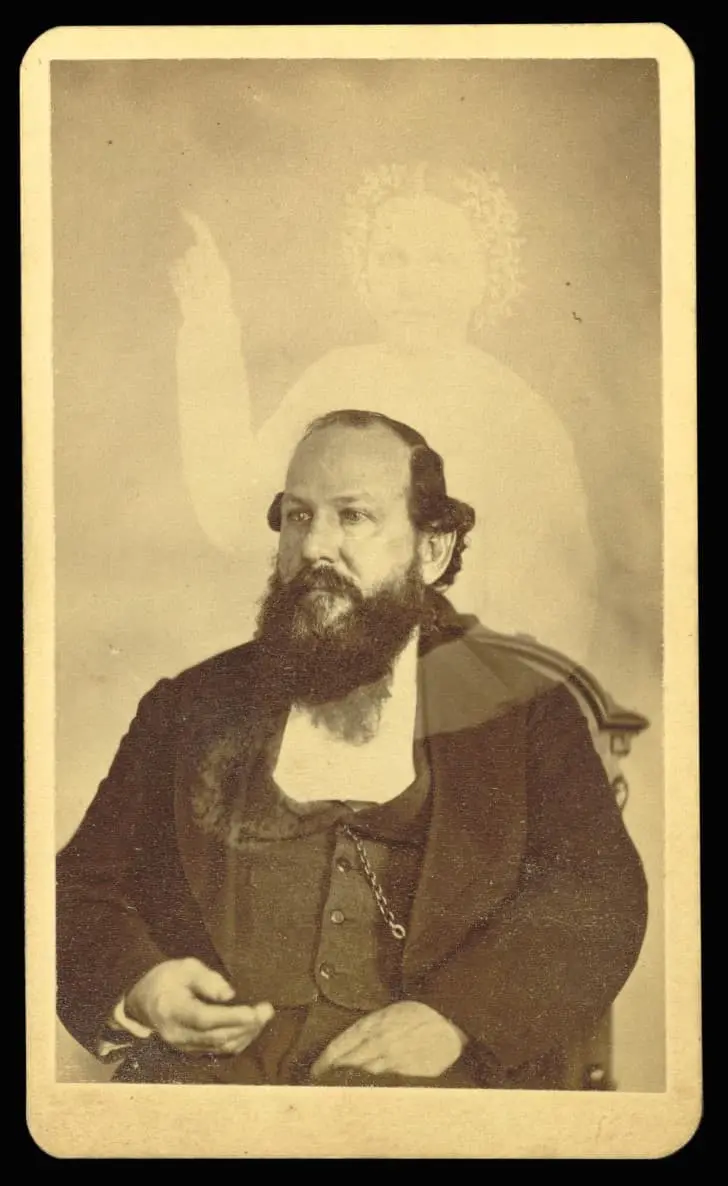

These photographs were something to be admired. A man named Luther Parks requested one of these photographs of ghosts, which featured him and another, more subdued image of a beautiful female spirit with a wreath of flowers on her head. In another work, a woman identified only as “Mrs. Snow” appears next to a ghostly image of her deceased brother, holding a musical instrument in his hands (the man had been making such items all his life).

In another request, “Mr. Taylor” requested a photograph of his son, who recently passed away, sitting on one of his hands (which he held in the air while the image was taken). Evidently, in the photograph that Mumler delivered, the specter of a little boy appeared just as requested by the client.

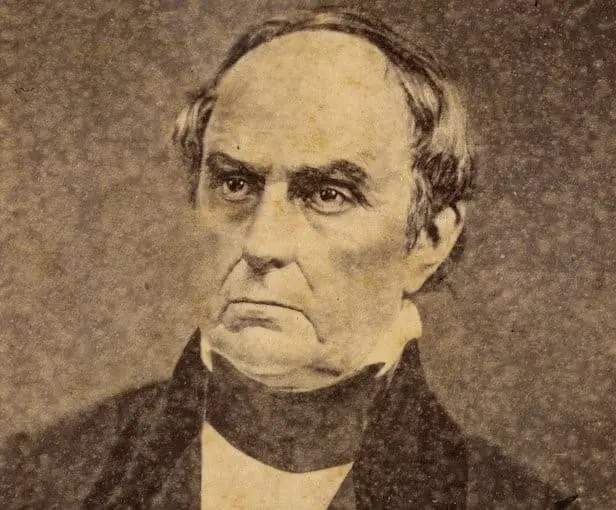

However, it wasn’t just family members who appeared in the ghost photographs. In one of the photographs of a “well-known citizen of Boston,” the unmistakable image of the recently deceased statesman Daniel Webster was manifested. And while many of the ghostly images weren’t easy to identify, most were convinced that the photographs featured dead relatives.

No one knew the technique used by Mumler to achieve those stunning photographs. In fact, other Boston photographers looked for ways to reproduce the technique using the same equipment, but the results were nowhere near it. One reporter went on to write an article from providing Mumler with his own photographic plate, to capturing the image, to developing it. In the end, the result was another ghost shot. The reporter concluded that the production of these spirit images was a mystery, and that their realization was something that neither deception research nor philosophy had the capacity to answer.

A supernatural gold mine.

However, Mumler wasn’t the only one in the family who profited from the paranormal. Hannah, his wife, offered her own services as a medium and all kinds of cures for the client who requested it. This woman claimed to have channeled on multiple occasions to the famous physician Benjamin Rush, who supposedly provided her with various cures for a variety of diseases. Of course, the specter of Rush next to her in the multiple photographs her husband took of her cemented her popularity as a psychic.

By early 1863, Mumler’s ghost photographs were already famous in America and Europe. The Photographic News, a popular London-based newspaper that published news about the world of photography, went so far as to review Mumler’s work. Noting the “considerable interest” they had with the photographers, the editor added a note with the possibility that it was a fraud.

True, Mumler had built up a solid base of supporters, but the Photographic Society of America quickly took a stance declaring that “spirit resemblances are a fraud and gross deception.” The British counterpart backed this decision. Also against Mumler were prominent skeptics, such as P.T. Barnum (a circus performer remembered for his notorious deceptions in the entertainment world). In 1866, Barnum published a book entitled Humbugs of the World in which he accused Mumler of being “pure smoke”.

William Mumler goes to New York.

However, Mumler’s ghostly photography business continued to grow, and he eventually moved to New York, where the most prominent photography experts could find no hint of fraud in Mumler’s work. William Mumler could not have worked at a time more conducive to the success of his business. The U.S. had been plunged into an atrocious civil war resulting in thousands of deaths and, consequently, family members desperate to find any proof that there was life after death.

The huge industry that grew up around spirit photography in the aftermath of the war not only caused many to put aside their disbelief. Other photographers also began producing their own photographs of ghosts when they saw the juicy profits Mumler was making. This did not even affect the photographer’s business, as the demand was huge and he had the luxury of charging much higher rates than the “non-spiritual” competition.

Although, not everything is forever. When New York Mayor A. Oakley Hall heard the rumors about Mumler’s work, he immediately commissioned an investigation. Chief Marshal Joseph Tooker went undercover to Mumler’s business and requested one of his ghost photographs. The result: an image of Tooker himself with a figure that would have been his father-in-law, according to Mumler himself. Tooker told him that the photograph “did not show anyone he had seen or known” and arrested him on charges of fraud and public deception.

The controversial trial of William Mumler.

In April 1869, Mumler appeared before Judge Joseph Dowling on two counts of fraud and one count of petty theft. According to the prosecutor, Mumler defrauded his clients “by means of tricks and devices with false pretenses, providing certain cards that he claimed were produced by spiritual and supernatural means, although he generated them with scientific and chemical means commonly used by individuals dedicated to the art of photography.”

The contentious part for the prosecutor was determining whether Mumler had committed the fraud on purpose, although there was no doubt that he was responsible for inflating the prices of his labor. However, that trial turned into a battle of two camps: those who believed in spiritualism and those who were skeptical. And in the middle of all the controversy were Mumler’s famous photographs.

This was the first criminal trial in which “ghost photographs” were presented as evidence. Thus, photography experts would analyze the way Mumler had created them to determine if he really had the ability to photograph the afterlife. Over the course of two weeks, more than twenty images underwent rigorous analysis.

The testimony of P.T. Barnum.

It is difficult to highlight the climactic moments of the trial, but without a doubt, the testimony of P.T. Barnum is among them. The consummate showman was extremely adept at captivating audiences, even in a courtroom, and he took advantage of this to convince them that Mumler’s photographs were a hoax.

In addition, he noted that none of Mumler’s clients seemed to have expressed curiosity that ghosts could dress in the same clothes that were fashionable on Earth. And, curiously, the clothes worn by the supposed dead evolved with the trends of the living, even though they had been underground for many years. He also recounted his experience with Mumler and how easily images could be faked.

Barnum’s testimony captivated everyone present, including the press, so the defense attorney tried to delegitimize him by questioning him about how long he had been making a living by deception. Barnum deftly dodged the question, and then he was questioned about his numerous frauds. However, none of this had any effect and Barnum triumphantly descended from the stand.

The conclusion of the trial.

After the presentation of all the available evidence, both the defense and the prosecution closed with extensive arguments covering the details of all the issues that arose during the trial. Mumler’s guilt about the fraud had already taken a back seat, and the debate seemed to focus on spiritualism, freedom of religion, the benefit that Mumler’s photographs had brought to bereaved customers, and the distinction between belief and truth.

In the end, Judge Dowling concluded that while it was possible that Mumler had misled his clients, he was not in a position to hold him liable for the evidence provided by the witnesses. Thus, he determined that he would not send him to the Grand Jury and released him.

The Last Years of William Mumler.

Although Mumler remained in the spirit photography business, the press kept calling him a “con man.” He returned to Boston deeply in debt as almost no one sought his services. Although this kind of photography enjoyed popularity for decades to come, the stigma around Mumler’s name nearly led to his complete ruin. Even those old photographs, acquired at exorbitant prices, were sold for pennies on the dollar. He survived on ordinary photography and went so far as to invent a process for producing photoelectrotype plates.

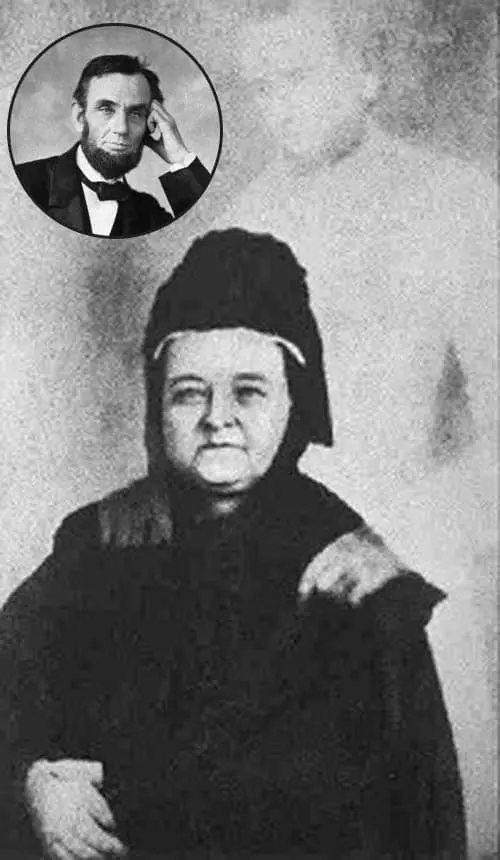

However, he continued to take some ghost photographs. One of his most famous clients in the last years of his life was Mary Todd Lincoln, the widow of the American president who introduced herself as Mrs. Lindall. Although the man in the photograph bears little resemblance to Lincoln, Hannah’s psychic intervention helped Mary convince her that he was her husband. This image provided Mumler with some breathing room and brought him new customers.

In May 1885, ghost photographer William H. Mumler died. His photographs of spirits were widely distributed in spiritualist circles after his departure, although most experts in modern photography disproved these works as forgeries.

Comments